Getting data

So far all the problems assumed that the data came from an existing file. But data can come directly from the internet without ever saving to a file. In fact, this is the most common way how commercial venues exchange data.

In practice, there are 2 main ways to obtain data:

- Scrpaing data from a website

- This is not recommended for reasons we will explain soon

- Calling the company’s API (application programming interface)

- This is the recommended route where agencies will provide some clear guidelines and filtering abilities.

Scraping a website

Most people are familiar with websites displaying information to them via their browser. To extract the information directly off the webpage is the act of scraping. We will only cover the most basic case where we parse the text information from the HTML information.

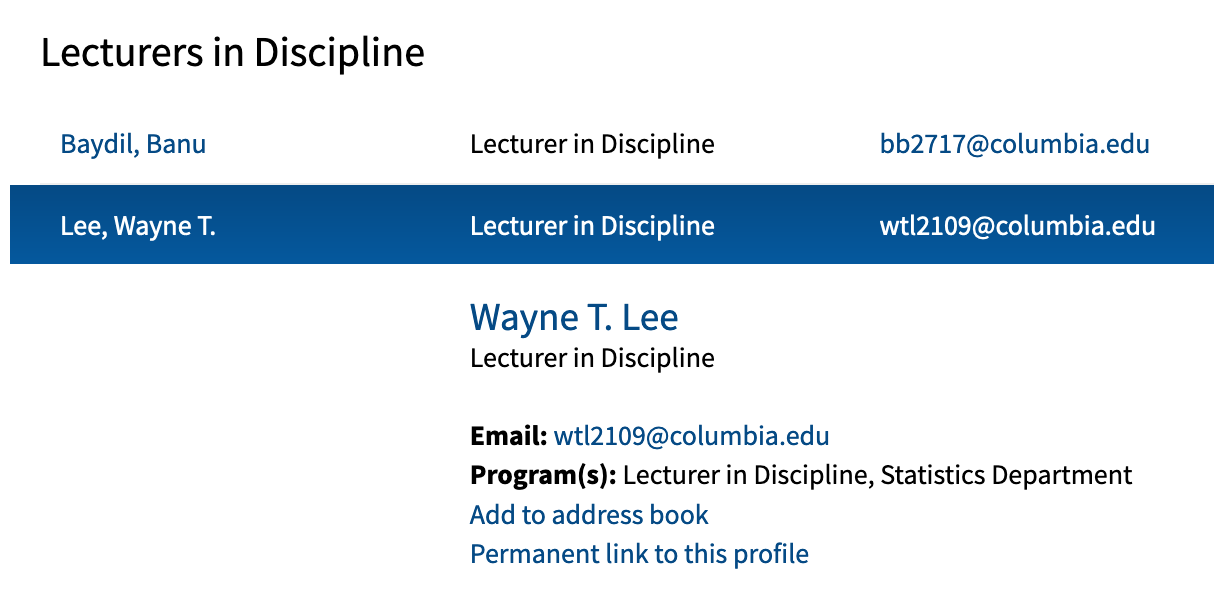

For an example, we’re going to obtain all the faculty’s names from Columbia’s Statistics department.

Specifically, we will try to get the bolded name like “Wayne T. Lee” and not the “Lee, Wayne T.” that is in an awkward ordering.

Using the inspector tool

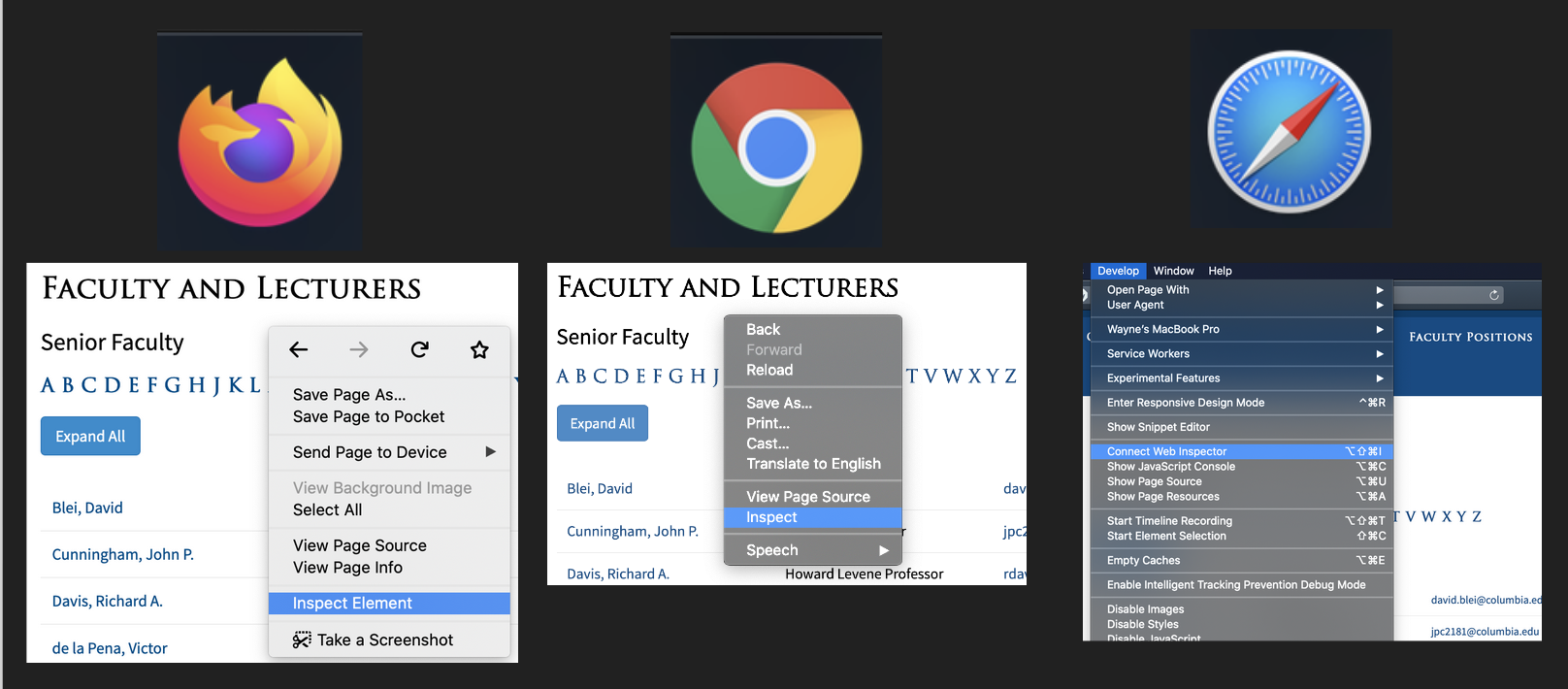

As of 2020, most browsers have an inspector tool:

The Safari “Develop” tab to show up by default, please Google how to get it to surface.

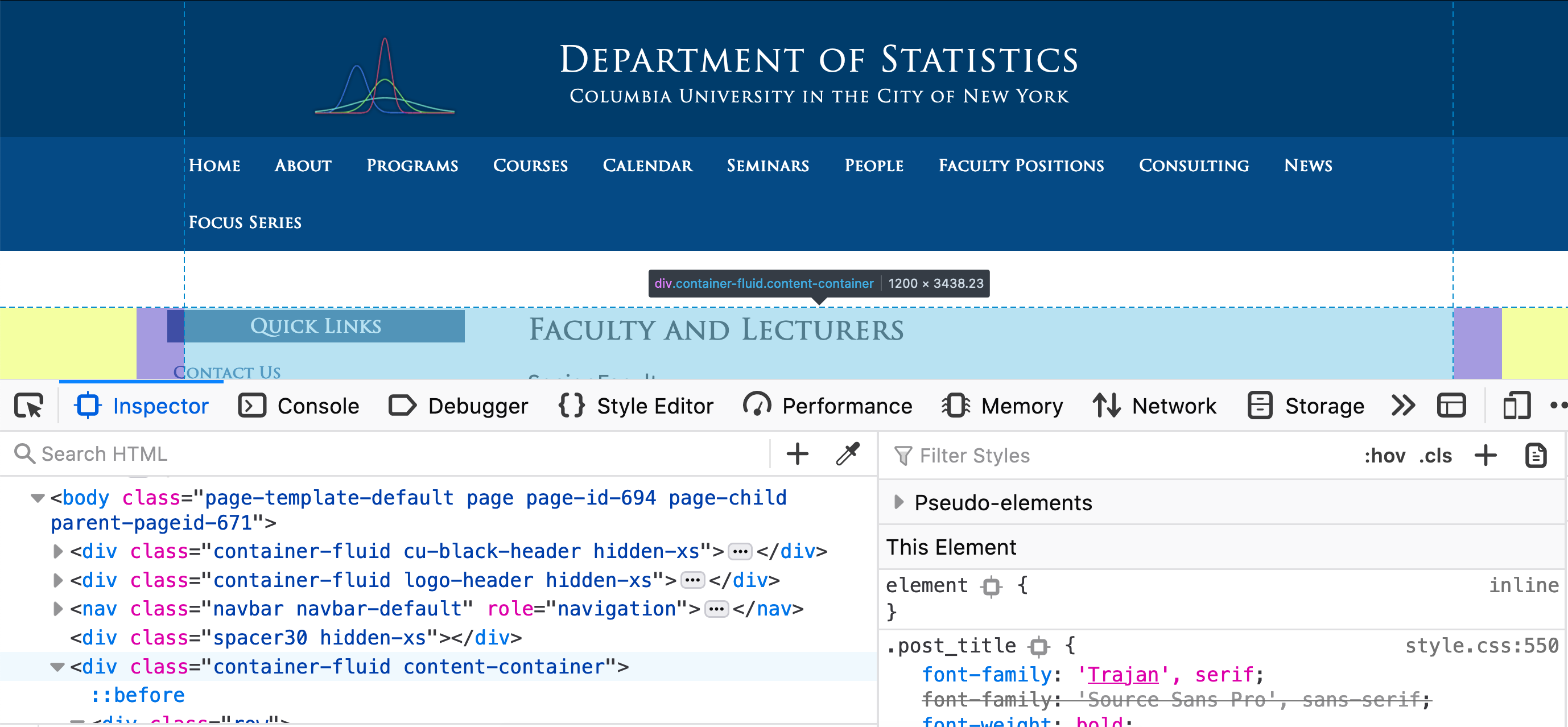

The inspector tool allows us to see what part of the code correspond to what part of the webpage.

Try moving the curosr around different parts under “inspector”, you should see different

parts of the webpage being highlighted.

At this point, we normally want to click into the different <div> tags (in Firefox, there are

dropdown arrows next to the <div> tags that hide the details within the tag) until we see only the

text of interest in highlighted. These tags similar to the comma in a CSV file where

they format the data so the browser knows how to display the content.

The information from the navigation will inform us how to write the code later.

A quick note about HTML format

In a loose sense, HTML is a data format for webpages (look up XML for the more proper data format).

Here are a few quick facts you need to know

- Most values are enclosed by tags, here’s an example using the

<p>tag:<p>Here is a paragraph</p>- Notice how we need a closing tag like

</p> - In Columbia example, you’ll see a lot of

<a>tags for hyperlinks

- Notice how we need a closing tag like

- Different tags have different purposes, for more information see here.

- HTML in general is hierarchical like nested lists because the webpage has different sections and sub-sections.

- The tags also have attributes, notice the

namein our Columbia example in<a name="anchor-36">is an attribute with a value set to"anchor-36"

Calling the webpage using R with httr

The HTML in the inspector tool can be obtained by using the GET() function

in the library httr.

library(httr)

url <- "http://stat.columbia.edu/department-directory/faculty-and-lecturers/"

web_response <- GET(url=url)

class(web_response)

names(web_response)

web_response$url

web_response$date

web_response$status_code

What to notice?

- We used the URL for the website and passed it to the function

GET() - You need to run

library(httr)beforeGET()will be available for use. - The class of the output from

GET()is not our usual data types. We will explore this later. - Various information associated with the call is attached to the output

- A

status_codeof 200 means the call was overall “successful”, other codes are ways to inform you of the type of error that was made.

- A

- If you peek at

web_response$content, notice that it’s in a weird format that you cannot read (encoded!)

To get the same text you saw in the inspector tool, you need to use content()

to help convert the binary data into text.

web_content <- content(web_response, as='text')

class(web_content)

substr(web_content, 1, 100)

length(web_content)

nchar(web_content)

Parsing the webpage using xml2

The converted text is extremely long despite being one single string. Its

format is HTML which is a close cousin to XML. Here we will need the package

xml2 to help us parse this string.

library(xml2)

html_tree <- read_html(web_content)

class(html_tree)

- Again we have a special class of data. The HTML data is often thought of as a “tree” or “graph” where the most outer layer is root node and you can dig into the child-nodes.

To get the names we will run the following:

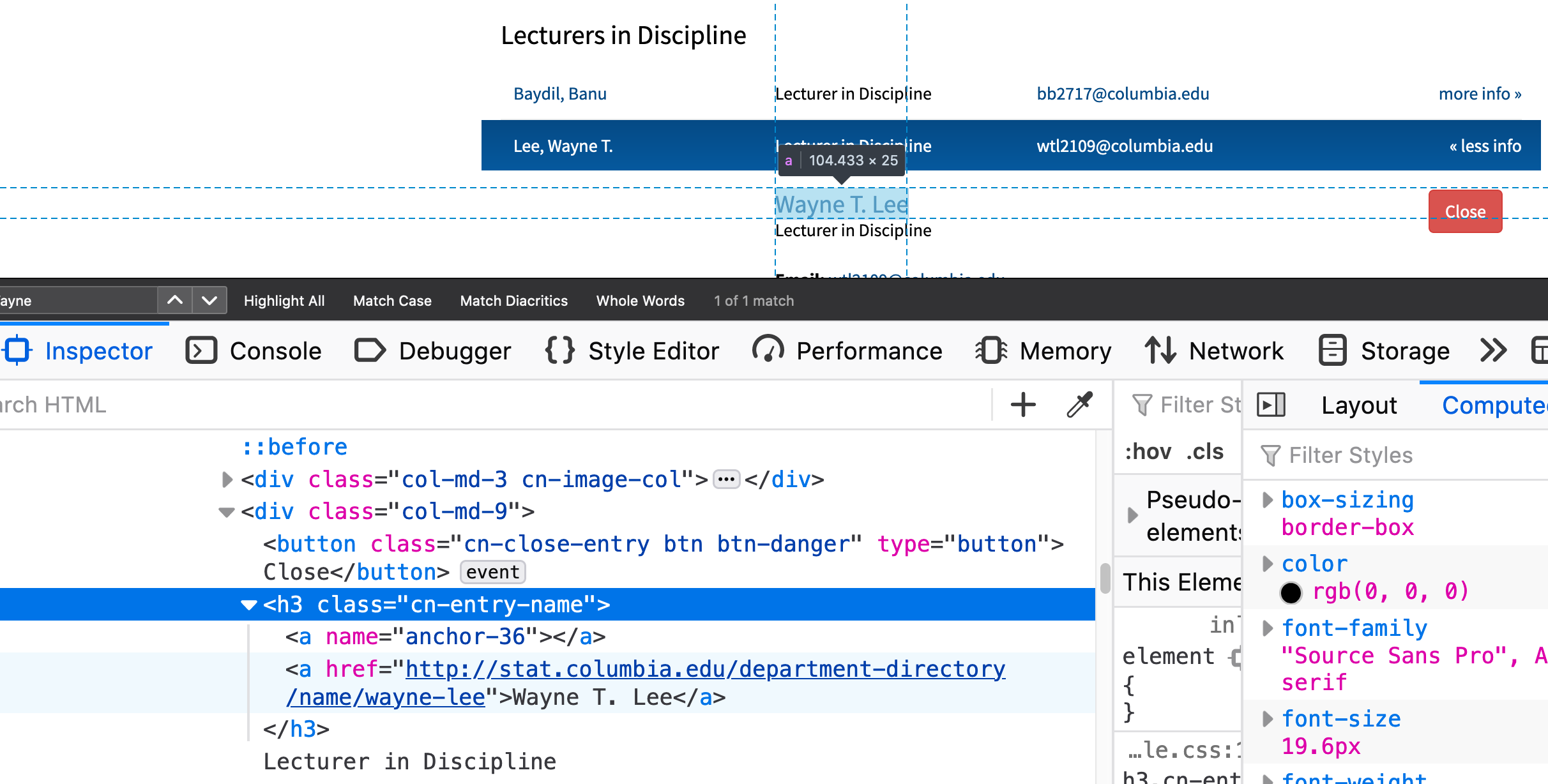

name_node <- xml_find_all(html_tree, xpath='//h3[@class="cn-entry-name"]')

length(name_node)

name_node[[1]]

- We used “xpath” to help us specify the nodes we want to find. “xpath” is a language to interact with xml data as regular expression is a language to interact with free text.

'//h3[@class="cn-entry-name"]'says that we want all the<h3>tags where their attributeclassis being assigned to"cn-entry-name". If you look back at our screen shot when navigating the inspector You’ll notice that the names are within the<h3>tag with certain attributes.- Notice we did not use the

<a>tag as our search because its attribute had faculty’s name in it which was what we were trying to find.

To complete the task:

name_link_node <- xml_children(name_node)

length(name_link_node[[1]])

all_names <- xml_text(name_link_node)

class(all_names)

all_names

- To get the names, notice how there are 2

<a>tags are within the<h3>tags, so we need the “children” of these tags, so we usexml_children() - Afterwards, we only want the text, not the information from the tag so we use

xml_text() - The final output is back to data types we are familiar with so we can use our methods above to handle these characters.

Side comment: scraping takes a lot of trial-and-error, do not worry if this took awhile to do!

From the special classes in httr and xml2 to our native R data types

Special data types are common in object oriented programming languages (which R supports) so sometimes you’ll see odd data types pop up.

These are created often to facilitate operations specific to the type of data at hand (e.g. parsing responses from websites, navigating XML graphs). Packages/libraries will often have custom functions that interact with these special data types (e.g. content(), xml_children(), etc).

My general recommendation is to:

- Find the examples in the documentation to leverage these custom functions

- Sometimes you’ll have to Google for examples/tutorials. Generally popular libraries will have plenty of tutorials available online. This is a reason to use libraries that are well-known even if you may not like how they’re coded up.

- Try to output the necessary information into a native R data type (e.g. numeric, lists, character, etc) that you are familiar with so you regain control over the data.

Side comment: custom data types and functions are common in something called “object oriented programming” (OOP) as opposed to function programming (where the data types are limited but the number of functions is vast). You should take a CS course if you’re curious about these 2 philosophies.

The “Network” under Inspector and why scraping is discouraged

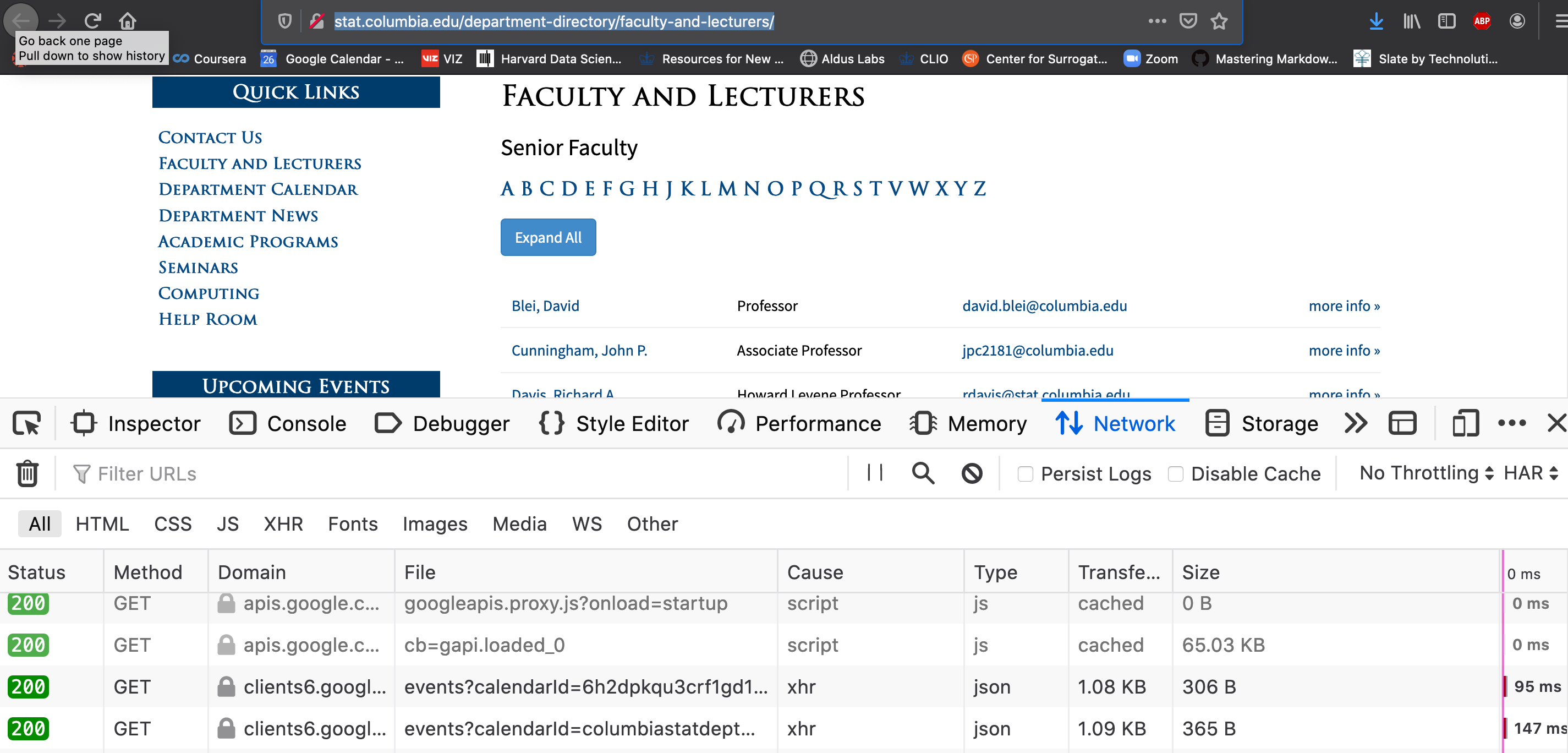

Return to the Inspector Tool, you should see a tab called “Network”.

- Click on the “Network” tab

- Refresh the faculty page

- Notice the activities triggered from loading a single page!

- Each of these line items is a “call” (e.g. how we ran

GET()above is a single call) to somewhere on the internet - You should see the time to finish each task, the size of data, and the “type” of data passing between your browser and the web

- Each of these line items is a “call” (e.g. how we ran

Take-home messages:

- When you load a website, a lot of activity is triggered so scraping is very resource intensive

- You are often unaware of what is being sent to/from these APIs that are being called (this is

how Ads track you)

- If you click around, you’ll notice that your browser, type of OS you’re using, your language preference and sometimes your general location information is being sent.

- Notice how images take up a lot of bandwidth (knowing this will help you be careful when dealing with image data)

Some context on APIs

Here are some of the flaws of scraping:

- From the company’s perspective, you scraping their website is wasteful to them.

- To us, scraping the data from their website is extremely unreliable (there are ways to make it much harder) because a simple change on the website will break our entire scraping algorithm (bad for automation). Also, the data may not be the data we want (imagine trying to get historical faculty members).

One way to solve this, is to leverage the company’s APIs:

- API stands for application programming interface, it’s something you can write code

against (programming interface) so you can interact with the company’s application.

- What does “write code against” mean?

- APIs are often provided with certain guarantees like “the data will be returned as a JSON with with certain attributes”. So even if the company changes their website, the APIs will often behave the same way so automated pipelines that rely on these data sources will not crash.

- What do you mean by the company’s application?

- Turns out a single website often has several different teams managing different features/applications. For example, on the homepage of LinkedIn, you can see news team, jobs, and posts from your your connections. The content for each category is actually created by different teams and one team then decides what/when to display to you when you login. The key is that different features/applications would then have access to different types of information/data and would naturally support different APIs.

- What does “write code against” mean?

Elements in an API call

Calling an API can be done via the GET() function as in scraping!

The common difference is that we will often pass multiple arguments along with our call

to specify who we are and what we want.

As an example, we will use the newsapi.org as an example. This is a website that aggregates different headlines from different papers. It gives you a few “free” calls but will block you after a certain threshold (freemium business model).

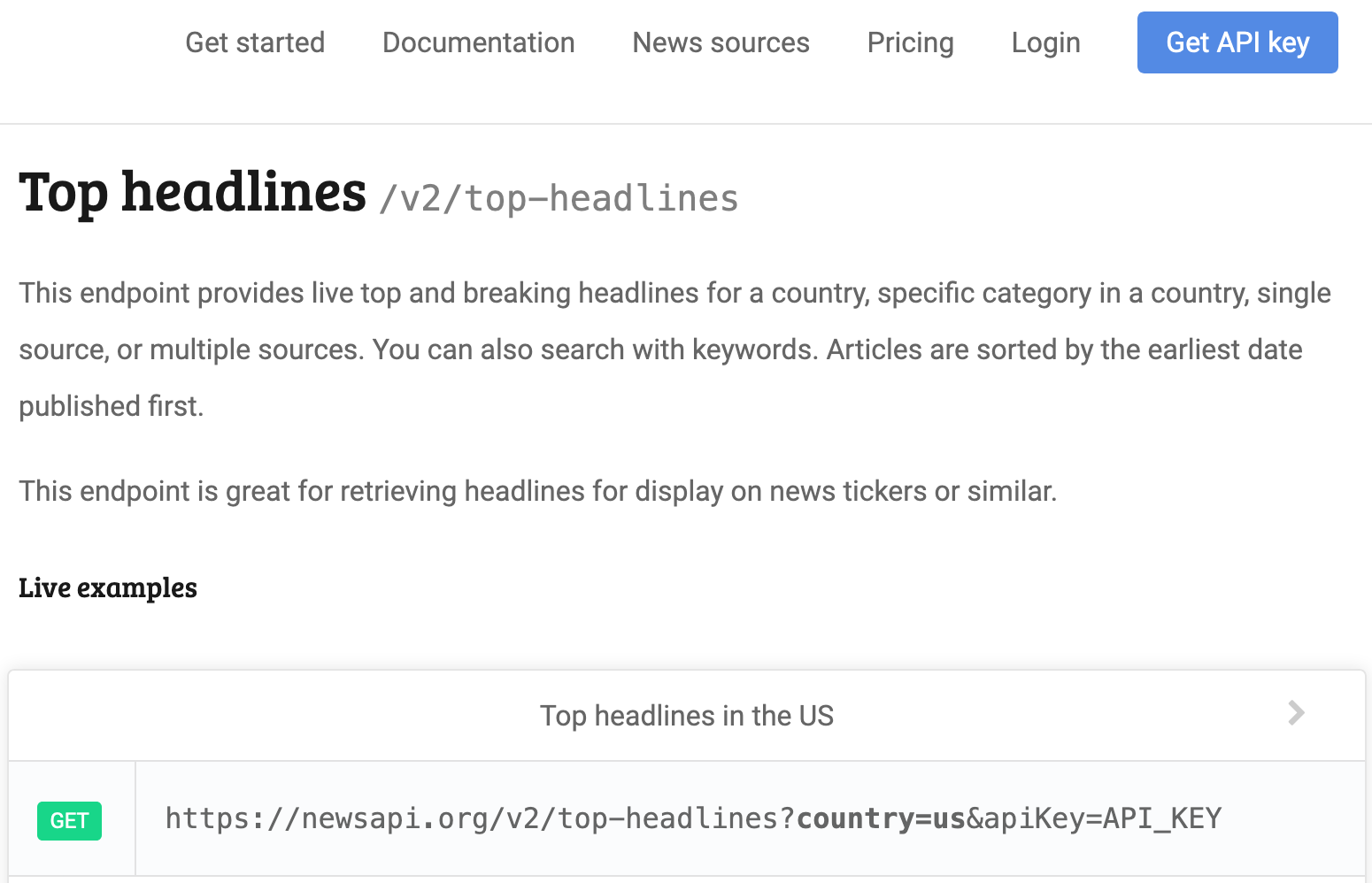

If you look at the documentation for NewsAPI.org, there are 3 different

urls, under “Endpoints”, for 3 different applications: top headlines, everything, and

sources. If you click on “Top headlines”, you’ll see a link, https://newsapi.org/v2/top-headlines?country=us&apiKey=API_KEY

after the word “GET”.

On the page above, the elements to make an API call are:

- The url: this is similar to the URL for your browser.

- For our example it’s the

https://newsapi.org/v2/top-headlineswhich is everything before the?

- For our example it’s the

- Parameters: these are like arguments to a function

- From the example, the parameters can be spotted after the

? - For our example, it seems like we can specify an argument named

countryand one possible value isus - You can find more arguments under “Request parameters” to see the names and the possible values.

- From the example, the parameters can be spotted after the

- Credentials:

- Notice one of the parameters is

apiKeythat is required yet its value is not provided. This will contain the credentials that are unique to you. You’ll need to apply for these by following the instructions on the right top corner. - This application process is unique to each company. Twitter’s process can go up to 2 weeks, we have chosen one that can be provided instantly.

- Some government agencies will not require you to apply for credentials.

- Notice one of the parameters is

Using httr to call the APIs

Now we know the elements, we will use httr to get the data similar to the example shown on

the NewsAPI.org Top Headline endpoint

library(httr)

url <- "https://newsapi.org/v2/top-headlines"

params <- list(

country="us",

apiKey="THE_KEY_YOU_GET")

response <- GET(url=url,

query=params)

response$url

response$status_code

newsapi_data <- content(response)

class(newsapi_data)

names(newsapi_data)

What to notice?

- We passed the url to the

urlargument inGET() - All other parameters, including the credential was passed to the argument

queryinGET()as a list.- The names used in the list are according to the parameters accepted by NewsAPI.org.

- Notice that we did NOT pass

countryandapiKeytoGET()directly because these arguments are specified by NewsAPI.org, notGET()

- Your status code should be 200 if you provided the correct credentials and everything.

- Notice that the

urlinresponsewas now formatted as shown in the documentation for us.- It is important that you let

GET()handle the formatting because symbols like “ “ or “!” need to be encoded differently. Your code is also easier to read this way.

- It is important that you let

- The final data should be a list that you know how to wrangle into a format that’s easy to analyze.

Common errors in calling APIs

- A

non-200status code. This often will have an informative error message. Try providing wrong credentials and see what happens. - Passing the arguments meant for the API to the

GET()function instead. For example:# Bad GET(url=url, country="us", apiKey="YOUR_KEY") # correct GET(url=url, query=list(country="us", apiKey="YOUR_KEY")) - Spelling mistakes in the argument, try passing

APIKEYinstead ofapiKeyabove, APIs tend to be case sensitive. - Hitting your cap or not following the rules specified by the company. The APIs require servers to be running in the backend which cost money. Companies will often restrict the maximum number of calls you can perform for free. Reading the error message will help you resolve this.

- Using the wrong url. Try adding a typo, see what error surfaces!

- Some places have firewalls that prevent you from accessing some APIs, this is complicated…

Wrapping up

Hopefully you see how you could get more data from different websites in a programmatic fashion, i.e. not clicking on Donwload manually.

I recommend you to try getting data via different APIs from different companies. Here are a few places to start: